Great Smoky Mountains National Park (93)

Great Smokies rangers levy fines against visitor feeding Cades Cove bear peanut butter

Written by Thomas Fraser A black bear makes its way through Cades Cove in this National Park Service photograph. This is emblematic of Smoky Mountain bears on the move in the spring; the park service recently took action against a visitor who fed a bear peanut butter in the area. The bear in question had been feeding on walnuts for several weeks prior to the visitors’ introduction of human food, attractions to which can doom black bears because they are more prone to exhibit dangerous behavior toward people and become habituated, and even dependent, on their presence.

A black bear makes its way through Cades Cove in this National Park Service photograph. This is emblematic of Smoky Mountain bears on the move in the spring; the park service recently took action against a visitor who fed a bear peanut butter in the area. The bear in question had been feeding on walnuts for several weeks prior to the visitors’ introduction of human food, attractions to which can doom black bears because they are more prone to exhibit dangerous behavior toward people and become habituated, and even dependent, on their presence.

Smokies visitor feeding bear peanut butter in Cades Cove was reportedly caught on camera. That aided park rangers’ search for the perp.

A visitor to Cades Cove thought it would be wise to feed peanut butter to a black bear in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and she got a ticket as a result. The person who received the citation, according to a news release from the park, was identified via video taken by another park visitor.

A National Park Service spokeswoman followed up with Hellbender Press the morning of June 8 in response to some questions. Rangers issued the citation to a 27-year-old woman, one of three adults in the vehicle. If the woman simply pays the fine and doesn’t contest it in court, she will pay a $100 fine, plus a $30 fee

Anyhoo, for Pete’s sake, don’t feed the bears. They’ve got enough problems without us getting involved.

“Managing wild bears in a park that receives more than 12 million visitors is an extreme challenge and we must have the public’s help,” said Great Smoky Mountains National Park Wildlife Biologist Bill Stiver. “It is critical that bears never be fed or approached — for their protection and for human safety.”

The full National Park Service release from Great Smoky Mountains National Park follows:

“Great Smoky Mountains National Park rangers issued a citation to visitors responsible for feeding a bear peanut butter in Cades Cove. Rangers learned about the incident after witnesses provided video documentation. Following an investigation, the visitors confessed and were issued a citation.

“Prior to the incident, the 100-pound male bear had been feeding on walnuts for several weeks along the Cades Cove Loop Road. The bear started to exhibit food-conditioned behavior leading wildlife biologists to suspect the bear had been fed. Biologists captured the bear, tranquilized it, and marked it with an ear tag before releasing it on site in the same general area. Through aversive conditioning techniques such as this, rangers discourage bears from frequenting parking areas, campgrounds, and picnic areas where they may be tempted to approach vehicles in search of food. This includes scaring bears from the roadside using loud sounds or discharging paint balls.

“Park officials remind visitors about precautions they should take while observing bears to keep themselves and bears safe. Until the summer berries ripen, natural foods are scarce. Visitors should observe bears from a distance of at least 50 yards and allow them to forage undisturbed. Bears should never be fed. While camping or picnicking in the park, visitors must properly store food and secure garbage. Coolers should always be properly stored in the trunk of a vehicle when not in use. All food waste should be properly disposed to discourage bears from approaching people.

“Hikers are reminded to take necessary precautions while in bear country including hiking in groups of three or more, carrying bear spray, complying with all backcountry closures, properly following food storage regulations, and remaining at a safe viewing distance from bears at all times. Feeding, touching, disturbing, or willfully approaching wildlife within 50 yards (150 feet), or any distance that disturbs or displaces wildlife, is illegal in the park.

“If approached by a bear, park officials recommend slowly backing away to put distance between yourself and the animal, creating space for it to pass. If the bear continues to approach, you should not run. Hikers should make themselves look large, stand their ground as a group, and throw rocks or sticks at the bear. If attacked by a black bear, rangers strongly recommend fighting back with any object available and remember that the bear may view you as prey. Though rare, attacks on humans do occur, causing injuries or death.

“For more information on what to do if you encounter a bear while hiking, please visit the park website at www.nps.gov/grsm/naturescience/black-bears.htm. To report a bear incident in the park, please call 865-436-1230.

“For more information about how to be BearWise, please visit www.bearwise.org. Local residents are reminded to keep residential garbage secured and to remove any other attractants such as bird feeders and pet foods from their yards. To report a bear incident outside of the park, please call Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency or North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.”

This story has been updated with information supplied by the National Park Service in response to questions about the case from Hellbender Press.

At least $35 million headed to Smokies for southern Foothills Parkway overhauls and maintenance facilities improvements

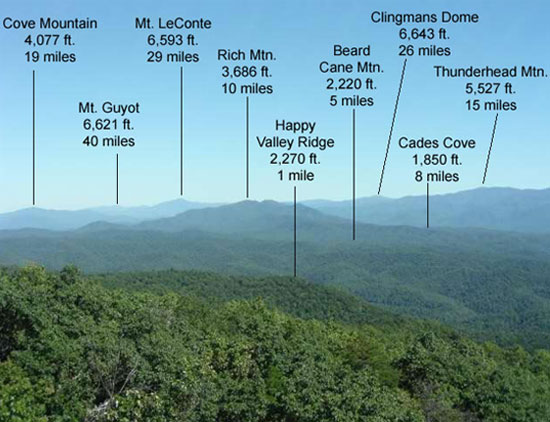

Written by Thomas Fraser The crest of the Smokies and its peaks are shown from Look Rock on the Foothills Parkway. National Park Service

The crest of the Smokies and its peaks are shown from Look Rock on the Foothills Parkway. National Park Service

Southern stretch of Foothills Parkway to get $33 million overhaul

The National Park Service will repave and improve the entire southern stretch of Foothills Parkway and design a replacement of the outdated maintenance facilities at Sugarlands thanks to funding from the Great American Outdoors Act.

Both projects will cost a combined $40 million and be paid for via a foundation established as part of the overall legislation passed by Congress in 2020.

The Department of the Interior will spend a total of $1.6 billion from the Legacy Restoration Fund this year alone as part of a long-range goal to improve infrastructure and catch up on maintenance needs in national parks and other federally managed lands, according to a release. National public lands across the country, including Great Smoky Mountains National Park, have long faced maintenance deficits totaling billions of dollars.

The Foothills Parkway and Sugarlands work is one of 165 deferred maintenance projects that will be funded this year. Infrastructure improvements are also planned for sections of the Blue Ridge Parkway and Shenandoah National Park.

The $33.6 million in planned improvements to the parkway between Walland and Tallassee (from mile marker 55 to 72) will include enhanced safety features and milling and replacement of the pavement.

“The road rehabilitation will include pullouts and parking areas, replacing steel backed timber guardrail, and repair, reconstruction and repointing of stone masonry bridge parapet walls and the walls along Look Rock Overlook,” according to interior department documents.

“Other work will include removing and resetting stone curb, replacing/repairing of the drainage structures, stabilizing roadside ditches, overlaying or reconstructing paved waterways, stabilizing and reseeding the shoulder, installing pavement markings, replacing regulatory and NPS signs, and constructing ramps with curb cuts to provide access to interpretive panels and to meet federal accessibility guidelines.”

“The work proposed in this project would reduce the hazards and improve safety for park visitors and employees,” according to the data sheet.

The Legacy Restoration Fund will also cover the $3.5 million cost of a design/build plan to improve and update the expansive and deteriorating maintenance yard at Sugarlands.

“The buildings, driveways, and parking areas associated with the maintenance yard have not been renovated or rehabilitated in decades,” according to a data sheet.

“There are safety hazards, inadequate space or capacity for park maintenance and operations personnel, and facilities that are entirely insufficient for essential park operations and maintenance. The condition of many buildings is so poor that replacement and disposal is likely the only practical option. This project will complete predesign project programming and budgeting and develop a Design Build RFP for the rehabilitation or replacement of facilities and associated utilities, parking, and grounds.”

Great Smoky Mountains National Park officials did not immediately respond to an email requesting additional information on possible future projects and to what extent national infrastructure plans proposed by the Biden administration might benefit the park, which is the most-visited in the nation.

Here’s a link to the full Department of the Interior National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund Fund release. Here are the Foothills Parkway and Sugarlands maintenance yard project data sheets.

Smokies bear vs. hog viral video: Yep. That’s about right.

Written by Thomas FraserSmokies biologist: Bear vs. hog video highlights nature taking its course

The days the Earth stood still (Part 1): Covid cleared the air in the lonely Smokies

Written by Thomas Fraser Great Smoky Mountains National Park Air Resource Specialist is seen at the Look Rock air quality research station. Courtesy National Park Service

Great Smoky Mountains National Park Air Resource Specialist is seen at the Look Rock air quality research station. Courtesy National Park ServiceThe lack of regional and local vehicle traffic during the pandemic greatly reduced measurable pollution in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

This is your Hellbender weekend read, and the first in an occasional Hellbender Press series about the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the natural world

Great Smoky Mountains National Park shut down for six weeks in 2020 during the Covid-19 pandemic. Recorded emissions reductions during that period in part illustrate the role motor vehicles play in the park's vexing air-quality issues. The full cascade of effects from the pollution reductions are still being studied.

Hellbender Press interviewed park air quality specialist Jim Renfro about the marked reduction of carbon dioxide and other pollutants documented during the park closure during the pandemic, and the special scientific opportunities it presents. He responded to the following questions via email.

Hellbender Press: You cited “several hundred tons" in pollutant reductions during an interview with WBIR of Knoxville (in 2020). What types of air pollutants does this figure include?

- great smoky mountains national park

- coronavirus

- smokies

- pandemic

- air pollution

- covid19

- air quality

- shutdown

- pollutant reduction

- carbon dioxide

- co2

- motor vehicle

- jim renfro

- nox

- voc

- improvement

- haze

- ozone

- look rock

- emission

- greenhouse gas

- visitation

- visitor

- traffic volume

- analysis

- monitoring station

- particulate matter

- mercury

- acid deposition

- quality control

- quality assurance

- so2 regional haze rule

- national park service

- nps

- air resource specialist

- ecosystem

- bioaccumulation

- so2

- road closure

- power plant

- epa

- environmental protection agency

Park service introduces permit system to protect Whiteoak Sink wildflowers

Written by Thomas Fraser

Park managers hope new rule will limit trampling of the flowers people flock to photograph. Meanwhile, there’s sad news about the sink’s resident bats.

Large groups of spring visitors to the geologically and ecologically unique Whiteoak Sink area near Cades Cove will have to obtain permits in an ongoing effort to prevent damage to the sink’s plant and animal habitats.

The sink is home to vivid wildflower displays in the spring, and the 5,000 people who come to see the annual spectacle stray off trails and destroy or damage some plant species.

“The intent of the trial reservation system is to better protect sensitive wildflower species that can be damaged when large groups crowd around plants off-trail to take photos or closely view blooms,” according to a release from Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Whiteoak Sink is off the Schoolhouse Gap Trail between Townsend and Cades Cove.

“This trial project will allow managers to determine if better coordinating group access can reduce trampling and soil compaction around sensitive plant populations.”

Update: Great Smoky Mountains National Park officials postpone controlled burn in Wears Cove to reduce wildfire fuel

Written by Thomas FraserPark service postpones 175-acre controlled burn

Citing low humidity and dry conditions, park officials postponed the planned burn until at least Tuesday along the park boundary in Wears Valley in the Metcalf Bottoms area. Another burn is planned near Sparks Lane in Cades Cove later in the week, depending on weather conditions.

Park managers plan a controlled burn along the park boundary in Wears Cove starting Monday. Don’t freak if you see heavy smoke in the area. March is an opportune time to conduct controlled burns for hazardous debris removal and habitat improvement in the interface between rural habitation and protected natural areas.

Fire prevention practices have become more widespread in Great Smoky Mountains National Park since a devastating and deadly November 2016 wildfire that spread into populated areas of Gatlinburg and Sevier County.

Here’s the straight skinny from the park service, per a release:

“Great Smoky Mountains National Park and the Appalachian-Piedmont-Coastal Zone fire management staff plan to conduct a 175-acre prescribed burn along the park boundary in Wears Valley to the Metcalf Bottoms Picnic Area. The burn will take place between Monday, March 8 through Thursday, March 11, depending on weather. Prescribed burn operations are expected to take two days.

A National Park Service (NPS) crew of wildland fire specialists will conduct the prescribed burn to reduce the amount of flammable brush along the park’s boundary with residential homes. This unit was burned successfully in 2009 and is part of a multi-year plan to reduce flammable materials along the park boundary with residential areas.

“A long-term goal of this project is to maintain fire and drought tolerant trees like oak and pine on upper slopes and ridges in the park,” said Fire Ecologist Rob Klein. “Open woodlands of oak and pine provide habitat for a diverse set of plants and animals, and the health of these sites benefits from frequent, low-intensity burning.”

Reckoning with racism with a walk in the woods

Written by Thomas Fraser

Video documents success of ‘Smokies Hikes for Healing’ endeavor

Great Smoky Mountains National Park Superintendent Cassius Cash was as shaken as the rest of us this past spring and summer when a national reckoning of racism erupted across the country following the homicide of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer.

Also like many of us, Cash, who is Black, wondered what he could do to help heal 400-year-old wounds.

He determined we needed to take a walk in the woods and talk about things.

“As an African American man and son of a police officer, I found myself overwhelmed with the challenges we faced in 2020 and the endless news cycle that focused on racial unrest,” Cash said in a press release distributed Feb. 26.

“My medicine for dealing with this stress was a walk in the woods, and I felt called to share that experience with others. Following a summer hike in the park, I brought together our team to create an opportunity for people to come together for sharing, understanding, and healing.”

Sixty people directly participated in Cash’s Smokies Hikes for Healing program, Smokies Hikes for Healing, which ran from August to December in the national park. Hundreds of people visited an accompanying website to learn more or acquire information on how to lead their own such hikes.

Cash, who credited the park team who helped him organize the innovative project, correctly determined there was no more appropriate place to honestly discuss racism and the importance of diversity than a hike in one of the most biologically diverse places on the planet.

David Lamfrom, Stephanie Kyriazis and Marisol Jiménez, facilitated the hikes and created a “brave space for open conversations about diversity and racism,” according to the park release, which also announced the availability of the Smokies Hikes for Healing video produced by Great Smoky Mountains Association.

Friends of the Smokies and New Belgium Brewing Company also contributed financial support to the effort.

A hellbender blends in perfectly against the rocks of a headwater stream. Rob Hunter/Hellbender Press

A hellbender blends in perfectly against the rocks of a headwater stream. Rob Hunter/Hellbender Press

Hellbenders get help in face of new challenges, increasing threats

Snot otter. Mud devil. Lasagna lizard. Allegheny alligator. For a creature with so many colorful nicknames, the hellbender is unfamiliar to many people, including millions of visitors to Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Julianne Geleynse wants to change that. The resource education ranger is tasked with teaching the public about the natural wonders the park protects within its borders in hopes of mitigating damage to natural resources caused by the millions of visitors, young and old, who enter the park each year.

With a visitor-to-ranger ratio of around 170,000 to 1, communicating with visitors is an ongoing challenge that requires unique solutions. Feeding wildlife and littering are perennial problems, but sometimes new issues emerge. Such was the case in 2017 — and again in 2020.

Heedless craze wreaked havoc

In 2017, researchers in the park were alarmed to find that hellbender numbers in traditionally healthy populations had dropped. An entire generation of subadult hellbenders seemed to be missing. The most glaring sign of the problem was the presence of dead hellbenders where visitors had moved and stacked rocks in park streams. Moving rocks to create pools, dams and artfully stacked cairns may seem harmless enough when one person partakes. But when hundreds of visitors concentrate in a few miles of stream every day for months on end, the destructive impact is significant. Viral photos of especially impressive cairns can spread on social media and inspire an army of imitators.

Why does moving rocks harm hellbenders? These giant salamanders spend most of their lives wedged beneath stones on the stream bottom. They live, hunt and breed beneath these rocks. In late summer, when temperatures still swelter and visitors indulge in their last dips of the season in park waterways, hellbenders are especially vulnerable as they begin to deposit fragile strings of eggs beneath select slabs. Simply lifting such a rock nest can cause the eggs to be swept downstream and the entire brood lost. As the researchers observed in 2017, moving and stacking stones can even directly crush the bodies of adult hellbenders.

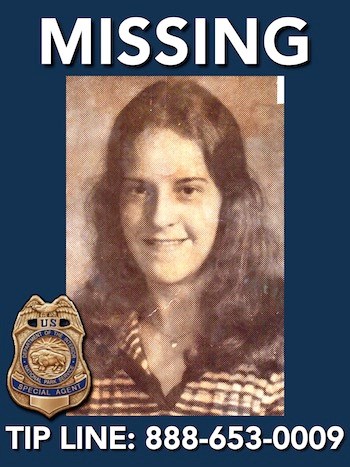

Into the Smokies: Mysteries persist in visitor disappearances

Written by Leslie Wylie

The western end of Great Smoky Mountains National Park as seen from Foothills Parkway. Thomas Fraser/Hellbender Press

Four visitors have disappeared without a trace from the Great Smoky Mountains in the last 50 years. Where did they go?

In a lateral move from late-night doom-scrolling, I’ve grown obsessed with reading about people who have gone missing in national parks. The National Park Service website currently lists 28 “cold cases” ranging from unsolved murders and suspected suicides to just ... gone. No body, nary a footprint or broken branch, no lingering scent for search dogs. Just poof. The silhouette of a life vanishing into mist.

I lie awake at 2, 3, 4 o’clock, hypnotized by the white glow of my phone, trawling abandoned blogs and conspiratorial subreddits for clues. I turn their disappearances over and over in my mind like a piece of quartz, glassy yet opaque, a fogged-up window I can’t quite see through.

Eight of these cold cases are from Yosemite, five are from the Grand Canyon, two are from Shenandoah Valley, and there’s one apiece from Mesa Verde, Crater Lake, Hawai’i Volcanoes, Yellowstone, Rocky Mountain and Chiricahua National Monument. Another four are from the Great Smoky Mountains, the wild and tangled backdrop of my east Tennessee home.

I’ve ventured furthest down the rabbit holes of the ones gone missing from the Smokies. Having spent a lot of time in the Park I’m familiar with the trails from which they disappeared. I’ve hiked them myself, one in an oblivious single-file search party of so many other Park visitors. It’s a strange feeling to know that you’ve literally walked along a path which, for someone else, led to … where did it lead?